MILANO-SANREMO 2021

MILANO.

It's the longest race of the Monuments. It's also famously known as the Monument that's (by far) the easiest to finish, but hardest to win. Starting in Milano at the Castello Sforzesco to the Via Roma in Sanremo - a world apart in a little more than 300km (with the entertaining neutral roll-out through Milano).

At this point in the season, riders are well on their way, and this is nowhere near the first race, but somehow, the start in Milano always seems to have those first day of school vibes. It's a fun start - full of smiles and relaxed riders. What's there to stress about? The riders have almost 200 kilometers before they really need to clock in for work.

At this point in the season, riders are well on their way, and this is nowhere near the first race, but somehow, the start in Milano always seems to have those first day of school vibes. It's a fun start - full of smiles and relaxed riders. What's there to stress about? The riders have almost 200 kilometers before they really need to clock in for work.

THE BREAK GOES.

After the twisty, bumpy, tram track ridden rollout through Milano, the race kicks off on the outskirts of the city - the break usually (in my experience) wrests free of the grasp of the peloton very soon after the red flag drops. Most years, the break is gone around Binasco - 10km into the race. From there, they have a long, long, long team time trial before rejoining the peloton somewhere around the Ligurian Coast.

THE DETAILS.

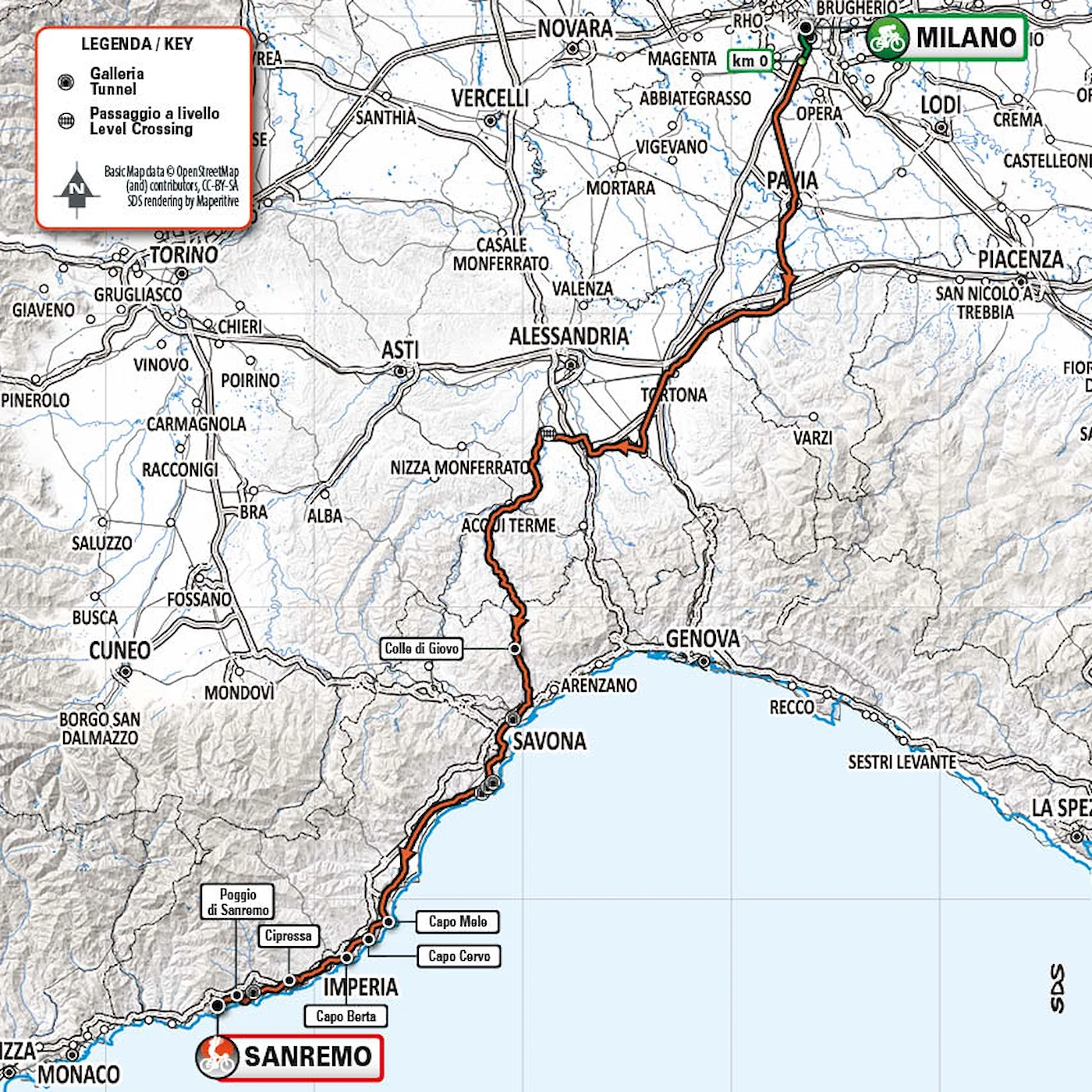

299km of racing from Milano to Sanremo. This year's route is back to more or less its normal flow after last summer's "special" edition. The big change will be the absence of the Turchino, which had to be taken out of the route due to a landslide. It's replaced by the Colle del Giovo, which will do the duties of getting the peloton to the Ligurian Coast. Even with that change, the rhythm is the same: the flat Lombard plain at the beginning, the crossing of the Appennini, the descent to the coast, then the Aurelia with the three Capi: Mele, Cervo, Berta, the Cipressa, and finally, the Poggio.

The excitement really kicks off with the Cipressa, before reaching meltdown levels on the Poggio. It seems all but certain that the cycling world will be wowed once again by some kind of thermonuclear acceleration from Mathieu Van der Poel, Wout van Aert, or Julian Alaphilippe. Or, if we're lucky, a combination of all three, as they feed off of each other's last effort.

The excitement really kicks off with the Cipressa, before reaching meltdown levels on the Poggio. It seems all but certain that the cycling world will be wowed once again by some kind of thermonuclear acceleration from Mathieu Van der Poel, Wout van Aert, or Julian Alaphilippe. Or, if we're lucky, a combination of all three, as they feed off of each other's last effort.

EARLY GOING.

I think it's safe to say that the opening part of Milano-Sanremo is not the prettiest. On a grumpy day, I might go so far as to say that it's ugly. I'm not grumpy today though, so I'll say that there are some nice spots along the way to get the photographers warmed up (as well as the riders, of course).

SHAPES.

Because we need a little palette cleanser.

PONTECURONE.

Our race chase of Milano-Sanremo always, always, always takes us through the lovely town of Pontecurone. Nothing has ever happened here, but it's always a fun spot to grab a coffee, brioche, a panino for later, and maybe just not leave the cafe and shoot from there.

THE BRIDGE

Not far after Pontecurone, there's an Autostrada bridge that crosses the course in a fun spot - because, when is it not fun to shoot from a bridge? Of course, this isn't exactly correct in the eyes of the law (I guess?), but there's a huge emergency pull-off, and the collection of fans, photographers, and people who pull over just out of curiosity makes for a great spot.

OBLIGATORY SANREMO SNOW SIDEBAR.

It would be a missed opportunity not to give a nod to one of the more memorable moments of racing in the last ten years. The snow of 2013. The race was stopped in Ovada after near blizzard conditions descended upon the field. It was restarted again on the other side of the Turchino in less snowy but no less miserable conditions. Gerald Ciolek of MTN-Qhubeka won that day in stunning fashion over the much favored Peter Sagan.

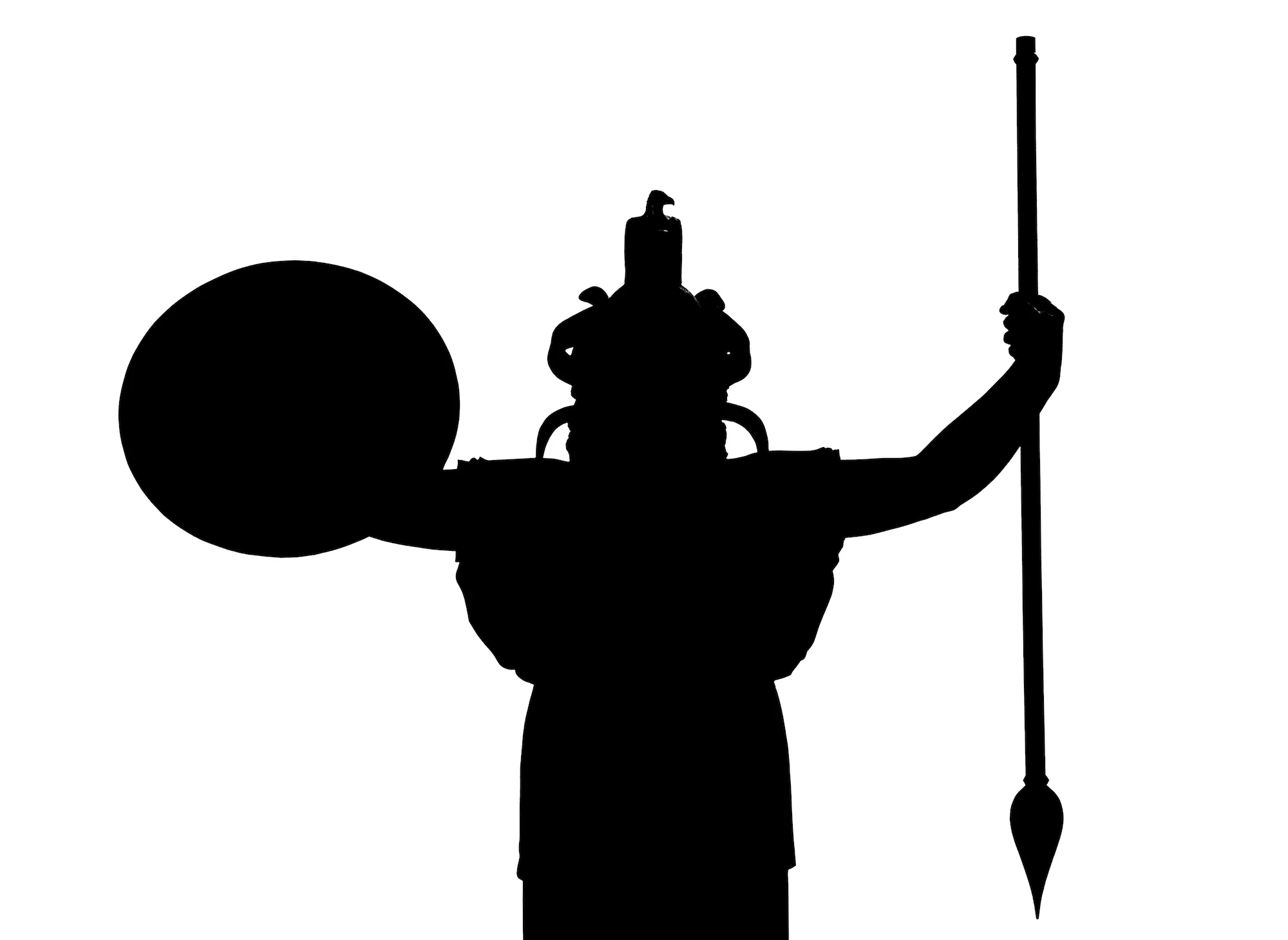

CROSSING THE APPENNINI.

Decades of the race have seen riders cross the Appennini by way of the Passo Turchino. In the early days, the Turchino was a decisive moment. In 1946, Fausto Coppi rode away from everyone on the Turchino and ended up winning by fourteen minutes. With approximately 40 kilometers to go and a ten minute lead, he stopped at the Caffe Piccardo in Imperia, leaned his bike against a wall, walked in, ordered an espresso, drank it, paid for it, remounted his bike, then added another four minutes to his lead en route to Sanremo to take a win that will forever live in the hall of legends.

This year, the race will miss the Turchino due to a landslide and take in the nearby Colle del Giovo. It's not the first time the Giovo has been used: for the exact same reason (landslide), Milano-Sanremo crossed the Appennini at the Giovo in both 2001 and 2002.

This year, the race will miss the Turchino due to a landslide and take in the nearby Colle del Giovo. It's not the first time the Giovo has been used: for the exact same reason (landslide), Milano-Sanremo crossed the Appennini at the Giovo in both 2001 and 2002.

TO THE COAST!

After a sinuous descent down to the Ligurian Coast, the riders take to the Via Aurelia and will follow it - more or less - to Sanremo (with a few notable detours to take on the Cipressa and Poggio). The coastal road is fast - and gets faster still as the racing begins to simmer and head ever closer to a full boil in the final hour. Along with the beautiful views, the route is marked by the three large hills - the tre capi: Mele, Cervo, Berta. They serve as an antipasto of sorts as the pace and tension ratchet up as they approach the first big appointment of the finale: the Cipressa.

LIGURIAN WONDER.

There's one spot in particular on the run along the coast that stands out above all others: the road between Noli and Novi Ligure.

CIPRESSA.

The Cipressa debuted at Milano-Sanremo in 1982 and did wonders in slowing down the avalanche of sprint finishes. It has become less of a critical spot in recent years, but it's still a crucial point in the race. The peloton reaches bunch sprint velocity in the run-up to the (on paper at least) tame 6km ascent that averages a hair under 4%.

THE POGGIO.

The final climb, the final launching pad, perhaps one of the more guaranteed thrilling climbs in all of cycling - was introduced to the route of Milano-Sanremo in 1960. It's barely a blip on the radar on a normal ride. It's not a hard climb at all. It's statistics are comical in this era of steep, steeper, steepest. It's 3.7km at less than 4% with a small section of 8%. And yet, it's a complete toss-up each year whether it will be decisive - will the aggressors get enough of a gap to make it to the finish - or will the peloton come back together for a field sprint in Sanremo? This year, it seems that the ball is firmly in the court of the attackers: if Van der Poel, Van Aert, and Alaphilippe can't get away from the sprinters - no one can.

SANREMO.

The riders reach the top of the Poggio with 5.5km to go. After an extremely technical descent, it's a flat, fast run-in to the finish on the classic Via Roma. The question is - and will always be - will then inevitable break or small split that has a small gap hold it to the line? Last year (2020), Van Aert and Alaphilippe managed to hold off the spring. In 2019, it was Alaphilippe who triumphed over an extremely select group; in 2018, it was Nibali - alone - in memorable fashion; in 2017, Kwiatkowski stole the day over Alaphilippe and Sagan. In fact, there hasn't been a big bunch sprint since Arnaud Demare won in 2016.

FINISH AREA SCENES.

In non-COVID years, the finish area in Sanremo is almost comical in its openness. Riders wade through the throngs of fans and curious bystanders, trying to get back to the team bus and some well-deserved peace and quiet after a long, long day.

FAVORITES.

Well, picking the blue chip favorites is pretty easy this year. It's the three-headed monster at the top of the heap in cycling that dominate the favorite slots, of course: Mathieu Van der Poel, Wout Van Aert, and Julian Alaphilippe. It's astonishing how good these three are - to such an extent that it's hard to imagine picking anyone else but one of those three. The first two are so good and have had such jaw-dropping seasons thus far, it almost feels like a stretch to include a nearly 100% Alaphilippe at the moment.

Of course, if it somehow does come down to a bunch sprint, and one, or two, or all three of the above don't storm the castle on the Poggio and a bunch sprint does somehow happen, the options grow a lot more. It seems that Sam Bennett is the man to beat in a field sprint at the moment. Normally, Caleb Ewan would be in this list too, but it feels kind of a back-handed addition when Wout just beat Ewan head to head at Tirreno in a field sprint.

Of course, if it somehow does come down to a bunch sprint, and one, or two, or all three of the above don't storm the castle on the Poggio and a bunch sprint does somehow happen, the options grow a lot more. It seems that Sam Bennett is the man to beat in a field sprint at the moment. Normally, Caleb Ewan would be in this list too, but it feels kind of a back-handed addition when Wout just beat Ewan head to head at Tirreno in a field sprint.

FOOTNOTES

Instagram: @jeredgruber / @ashleygruber

Instagram: @jeredgruber / @ashleygruber